South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, continues to be tormented by profound political instability, ethnic disintegration, and violent cycles. Power-sharing deals and peace agreements are necessary, but the foundations of lasting peace must be established at the grassroots level, among the people themselves. Citizens are not mere bystanders in the pursuit of peace; they are frontline players. Their role in rebuilding communal confidence, healing ruptured relationships, and abandoning violence is more vital today than at any other time.

South Sudanese political conflicts have always spilled over into ethnic violence. The Dinka and Nuer, with deep-seated tensions fueled by political affiliations, have suffered repeated cycles of revenge killings. The Toposa and Didinga in Eastern Equatoria have long battled over cattle raids and border disputes. In Upper Nile, Shilluk-Nuer tensions over land and exclusion from the political process have carved deep scars into social cohesion. The Murle and Dinka, however, have found themselves ensnared in cycles of child kidnappings and cattle raids that leave reprisal attacks in their wake.

Trust collapse among communities fueled by governance failures, youth militarization, and resource competition has spawned a precarious and perilous environment in all of these cases.

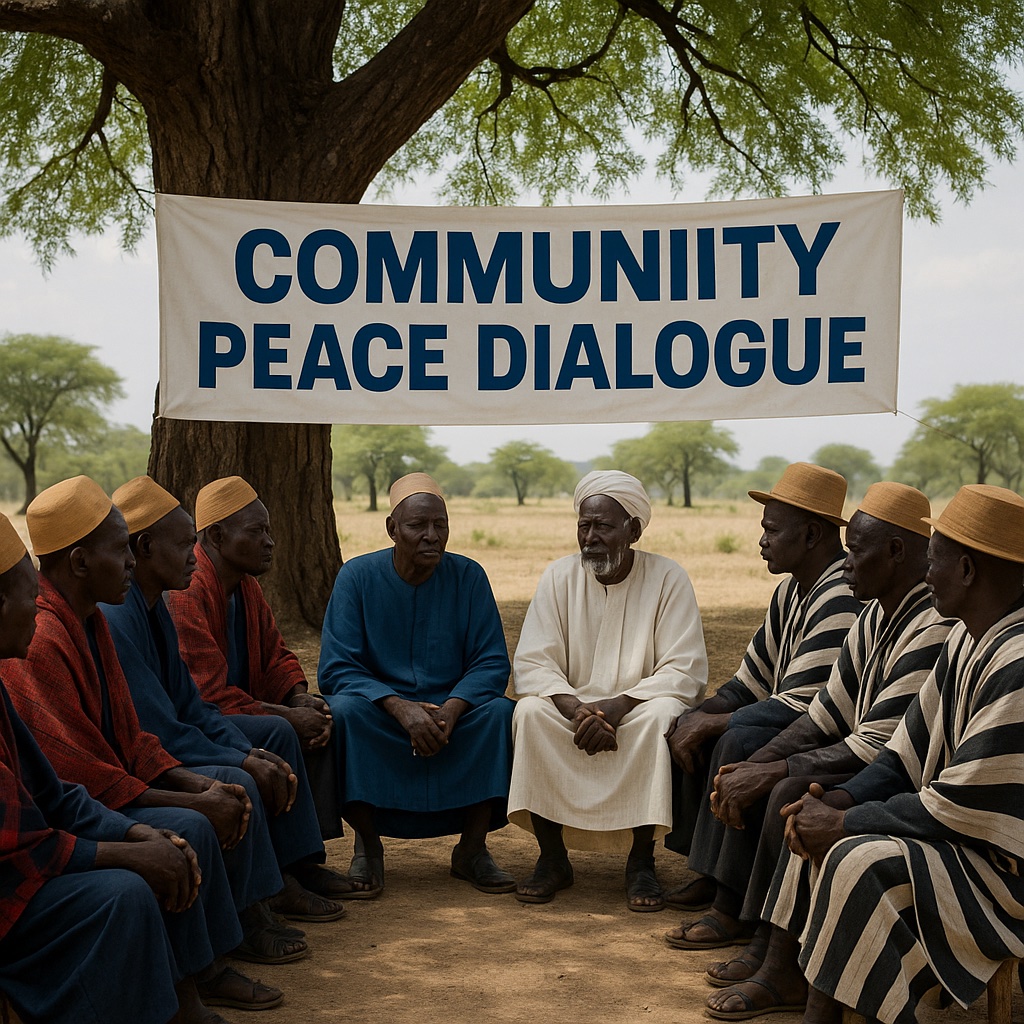

Peacebuilding at the local level is a task that needs to be undertaken by the people who live in or the immediate surroundings of conflict-prone areas. Such can include the following practical interventions:

- Conducting inter-community forums, including Dinka-Nuer elder conferences in Jonglei or Toposa-Didinga youth forums in Kapoeta and Budi counties. Forums offer room for airing complaints and solutions through peaceful means.

- Encouraging community peace agreements. For example, citizens can lobby for reinstating and implementing agreements like the Lafon Peace Accord between Toposa and Didinga.

- Establishing joint cattle guarding committees to prevent theft and retaliatory attacks between the Murle and surrounding groups like the Dinka Bor and Lou Nuer.

When citizens initiate the mediation process and take pragmatic actions, they reduce dependence on political elites interested in prolonging tensions.

Mutual peaceful living cannot thrive where communities believe in the notion of having to control the other. Citizens must contest:

- Hate speech broadcasted on local radio or social media that portrays ethnic groups as enemies.

- Political discourses in the language of ethnic identity versus militia or party loyalty.

Citizens, on the other hand, need to cultivate inclusive discourses. Dinka, Shilluk and Nuer youth and women in Malakal, for example, can engage together in communal clean-up operations or trauma-healing workshops so that they dehumanize and humanize one another and come to appreciate the ability to coexist.

Voting for leaders based on policy and integrity, not tribal identit can help dismantle the political system of ethnic patronage that keeps communities hostage to war.

Reconstruction after war must be seen as a shared responsibility. Both former warring communities’ citizens can:

- Volunteer side by side to rebuild roads, schools, or health centers, as seen in parts of Warrap and Lakes, where community service projects helped to reconcile enemy clans.

- Organize mutual youth peace clubs, where Dinka, Murle, and Nuer youth engage in sports, arts, and civic education to forge unity.

By working together on common goals, trust is gradually regained, and communities begin to understand each other not in terms of past conflicts but shared visions.

Women and young people are often both the victims and unsung heroes of post-war reconstruction. Women-led initiatives such as those initiated by Shilluk mothers in Upper Nile and Murle women in Pibor have been central to campaigns for the release of kidnapped children and to healing communities.

Youth can be taught nonviolent communication and act as peace ambassadors in conflict-affected areas such as Jonglei and Upper Nile, where they can be utilized to carry messages of reconciliation at community functions and local media broadcasts.

South Sudan is blessed with indigenous traditional peacebuilding practices. Citizens should urge their elders and chiefs to:

- Establish public truth-telling forums, such as those traditionally done among the Didinga and Toposa, to address past grievances.

- Facilitate communal forgiveness rituals with symbolic acts such as the offering of a white bull, which in the past has represented restoring harmony.

Such mechanisms, rooted in culture, offer legitimacy and healing where official justice mechanisms are absent or ineffective.

Citizens may also serve as bridges between national governments and the grassroots:

- State governments or peace monitors may receive community reports from local authorities in Unity or Jonglei.

- Peace committees may document incidents of violence and displacement so that the national peace compacts reflect people’s actual life.

- Citizens, by staying engaged, keep elites on their toes and prevent them from ignoring people’s needs or fueling the fire of war to pursue a political agenda.

South Sudan’s journey to lasting peace cannot be premised on power-sharing pacts, government reshuffles, or military neutrality. True peace, the lasting peace, demands a shift in how communities approach each other. It requires citizens to abandon hate politics, transcend inherited hatreds, and engage in everyday acts of reconciliation, justice, and healing.

Whether a Nuer farmer helps his Dinka neighbor rebuild a home, a Didinga youth coordinates a football game with Toposa players, or Shilluk and Nuer women insist on safe schools for their children, the seeds of peace belong to the people.

Let it be clear: South Sudanese citizens are not victims of war; they are the solution to its end.